Researching Community Engagement Against Violent Extremism: Lessons from the Field in Northern Ghana

Violent extremists (VEs) have been on the southward march from Niger and Mali into neighbouring Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Togo, and the Benin Republic since 2015. Although Ghana has not experienced VE attacks, its minimally protected 2,444-kilometer border is vulnerable to infiltration by VE groups. In 2017, the Government of Ghana launched the Accra Initiative as a security sector response to halt the advancement of VEs toward West Africa’s coastal countries.1 In 2021, the government launched the “See something, say something” campaign to encourage “the public to be vigilant of the activities of suspicious characters and report such activities and characters to the security agencies.”1 A cardinal presumption of the campaign is that citizens can easily recognize or identify the “suspicious characters” they should look out for. However, a 2021 study commissioned by the National Commission on Civic Education (NCCE) on the risk/threat of VE in Ghana established that “the term violent extremism was not clearly understood by the majority of the primary respondents.”2 This raised concerns about what citizens, especially those in rural areas, know about VE and how prepared they are to engage in the actions suggested in the See Something, Say Something campaign.

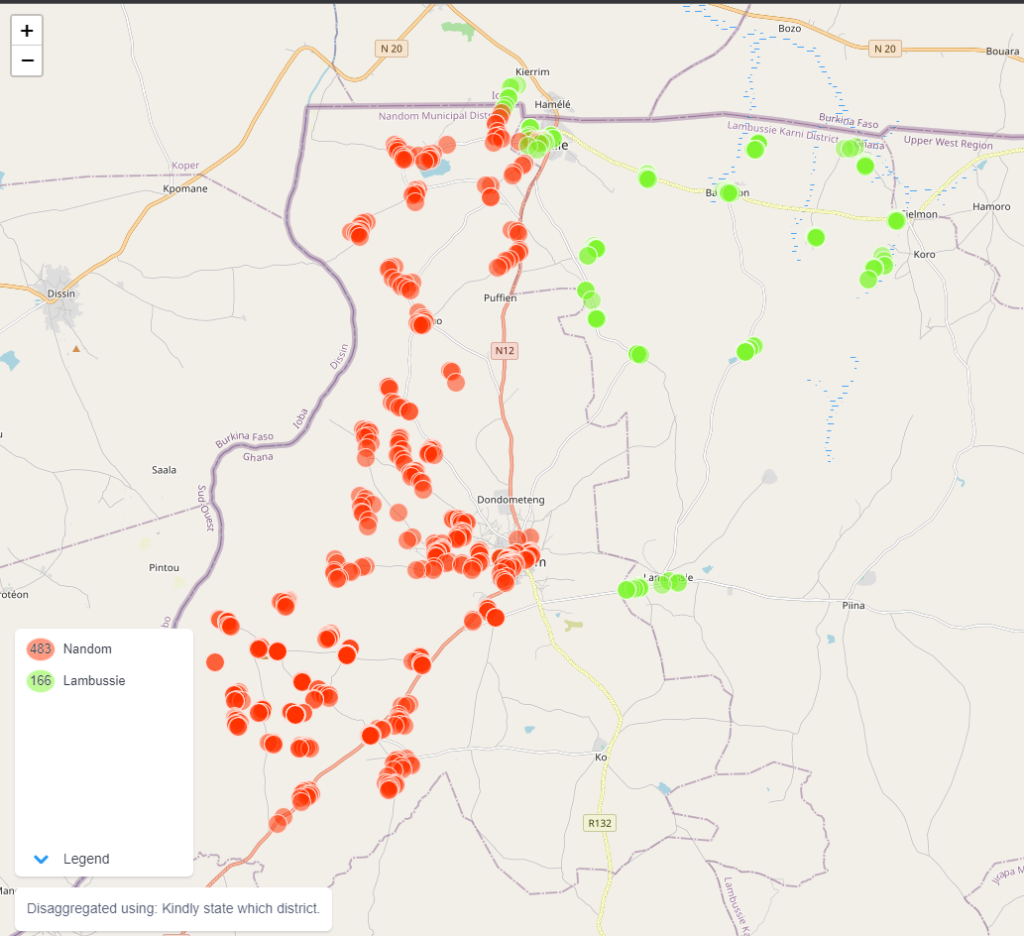

The Social Science Research Council (SSRC) through the African Peacebuilding Network (APN) provided an individual research award in support of my research project seeking to investigate concerns raised by the NCCE study in relation to border communities3 in the Nandom Municipality and Lambusie District of northern Ghana. The NCCE study interviewed 17 participants in the Nandom and Lambusie-Karni areas out of 1,173 nationwide interviews. This small number of interviews did not fully capture the voices and views of community-level people living the daily experiences of trans-frontier movement of persons, with the potential infiltration of VEs. Hence, I used the funding from the individual research award of the APN to leverage the support of the Institute for Peace and Development (IPD), Tamale, to develop a deep dive study that recruited, trained, and deployed 22 data collection agents (DCAs) to conduct 649 individual surveys, 93 key informant interviews, and 51 Focus Group Discussions in 67 communities over a period of 16 working days in the Nandom Municipality and Lambusie-Karni district (See Appendix 1 for study sites). The DCAs used online data collection platforms to collect and upload data that enabled daily quality checks and validation of the data collected. They were also trained to observe what was going on in the communities they visited, take notes, and hold debriefing sessions every evening with Field Supervisors. Their observations were collated into written reports that formed part of the dataset for the study.

The data collection process showed how the field can affirm or question the value of a research project. In many communities, participants indicated that the study was the first time anyone had come to them to seek their views on what they could do to help prevent VEs from coming into Ghana, even though they see persons moving across the borders on a daily basis. They recounted how once in a while police or military vehicles would drive through their communities toward the Black Volta for a few minutes and then drive back without stopping to greet or interact with them.

Community members were very much invested in the objectives of the study and were willing to help. In Guri, they offered to show us multiple pathways to the river traversing Ghana and Burkina Faso if we were ready to muddy our feet. We took them up on the offer. Once we got to the river, local fishermen and canoe transport operators offered us an unprompted free ride across the Black Volta into Burkina Faso to show us how easy it was to commute between the two countries on the blind side of security services. We accepted their offer.

At the Dabagteng community, we witnessed the porosity of the Ghanaian border when a citizen of Burkina Faso arrived at the banks of the river on the Ghana side with goods on his bicycle. He made a “coo” sound, and a canoe taxi operator on the Burkina Faso side abandoned the fishing nets he was mending, crossing over in his canoe to give him a ride across to the other side. In a conversation with the Burkinabe traveller, he explained that crossing the river for business and social events was a normal act, since “we go to each other’s markets and attend each other’s social events such as funerals.”4 For Burkinabe and the Ghanaian fisherman/canoe transport operator, the national boundaries exist only in the minds of government officials.

While the porosity of the border enabled easy movement and social interactions across borders, this comes with potential security problems. As if to underline the urgency and timeliness of our research, on December 7, 2022, a week after the data collection ended, VEs attacked communities in Burkina Faso close to the border with Ghana, displacing at least 796 persons into communities in northern Ghana.5 Those running away from the VE attacks in Burkina Faso simply poured into their neighbouring communities without let or hindrance. Host communities in Ghana received them without question. They only alerted government agencies because they needed material support to take care of their new guests. Community members also immediately called our DCAs who had visited them to alert them to the incident. IPD dispatched two data collectors to return to the communities to conduct interviews with the displaced persons. The communities’ outreach to the research team demonstrated the level of faith and trust that they had in the study’s ability to accurately represent their lived experiences.

Lessons of the Field

Although data analysis is ongoing, research-based observations and insights from study communities are already very instructive regarding the state of unpreparedness of frontier communities to prevent or counter VE infiltration into Ghana. Frontier communities understand their vulnerability to VEs attacks from the open, unprotected, and multiple unofficial crossing points along Ghana’s borders, but feel neglected, unengaged by the government, and helpless in preventing or countering VE activities in and through their communities. They may have heard of VEs, but do not know what or who to look out for. They realize they may be unwitting accomplices to VEs by the services they provide but cannot tell VEs from their benign neighbours travelling for trade or social events. Through our interactions with them, they showed us how hearing about VE is not enough to trigger engagement with the government and other stakeholders. They need more information and engagement to be active participants in the fight against VEs.

Conclusion

Drawing on the experiences from our fieldwork, we recommend the following to the government and other stakeholders

- Improve Accuracy, Completeness, and Consistency in CPVE messaging: Most respondents got their knowledge about VEs from sources such as the radio, friends, and during attendance to churches and mosques. However, there is no deliberate effort to ensure these channels of information, communication, and education on VEs have complete, accurate, and standardized content of the VE education messages they share. To ensure complete and consistency in community CPVE education and mobilization, we recommend that NCCE and CPVE education actors consider:

- Engaging mass media houses in content development and dissemination to ensure all local broadcast stations have the level of complete and accurate information to convey to members of the public.

- Harnessing Indigenous Channels of Communication: Respondents cited churches and mosques as their major sources of CPVE education. To ensure completeness and consistency in messaging, we recommend that duty bearers in the CPVE intervention space design and deploy special content training programs for religious leaders to adopt in their messaging on VE prevention in their mosques and churches.

- Investment in community policing: With minimal investments in training community-level actors in surveillance and reporting techniques, community-level actors can become more effective eyes and ears of the security services in their respective areas.

- Changing community engagement strategies to emphasize using more community-based (rather than radio-based) approaches such as durbars and community meetings to directly engage frontier communities

- Engagement of Cross-frontier Communities in CPVE initiatives: As with the military side of the Accra Initiative, effective community engagement in the prevention of VE travels and attacks cannot be a one-country affair. Communities on both sides of the borders of Ghana and Burkina Faso need to be fully mobilized and engaged to make CVE effective. To this effect, we recommend that municipal and district authorities in Ghana initiate cross-border engagements with counterpart administrative units on the Burkina Faso side to create platforms of information sharing, early warning, and risk assessment systems on VE activities within and between their communities. This is particularly possible and doable because of the existing cohesiveness of ethnic, customs, traditions, and linguistic affinities of people living across the borders in neighbouring countries. Additionally, shared economic spaces such as markets, fishing zones on the Black Volta, and trade between people across the borders create shared interests and independencies that predispose communities to work together to protect their common assets, and advance shared peace, security, and economic interests. Consequently, the initiation of cross-border engagements with the same messaging and activities will be a very effective way to build broader community response capacities to CPVE.

Author: Hippolyt A.S Pul, PhD.

References

- Kwaykye, Sampson, Ella Jeannine Abatan, Michael Matongbada, “Can the Accra Initiative Prevent Terrorism in West African Coastal States?” Institute for Security Studies (South Africa), September 30, 2019. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/can-the-accra-initiative-preventterrorism-in-west-african-coastal-states

- Abbey, E. E., ‘”See something, Say something’ campaign launched,” Daily Graphic Online, General News, May 25, 2022, available from https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/see-something-say-something-campaign-launched.html

- National Commission on Civic Education (NCCE), Risk/Thread Analysis Of Violent Extremism In Ten Border Regions, 2021, accessed from https://www.nccegh.org/publications/research-reports, p. xiii

- Frontier communities were defined as communities in the Nandom Municipality Lambusie-Karni District that lie within 5 kilometers from the Ghana-Burkina Faso Border.

- Conversation with Burkinabe traveler on the ease of trans frontier travel and trade, held at the banks of the Black Volta, Dabagteng Community, on 9 November 2022

- Balu, M, “796 flee in Burkina Faso to Sisala West Communities for fear of attack,” Ghana News Agency, December 7, 2022, accessed from https://gna.org.gh/2022/12/796-flee-burkina-faso-to-sissala-west-communities-for-fear-of-attack/

Hippolyt A.S Pul, PhD is a multidisciplinary scholar-practitioner with more than 35 years of work in international development planning and management. He is the Executive Leader of the Institute for Peace and Development (IPD– www.ipdafrica.org), which provides knowledge creation and learning services to a broad range of national and international development agencies and actors to support evidence-based, inclusive, and holistic intervention planning, management, learning, and accountability. Hippolyt’s research and service interests focus on the complexities in the intersections between governance, socioeconomic development, social cohesion, conflict, and peacebuilding programming. He has led many consultancy services and published journal articles, book chapters, and presented conference papers on issues that bridge over the different sectors of his research and work interests. He holds a PhD in International Conflict Analysis and Resolution; a master’s degree in public and social Policy; and several postgraduate certificates and diplomas. Hippolyt is a recipient of the 2022 APN Individual Research Fellowship Award, and he lives and works out of Ghana.